What the History of prostitution can teach us about human trafficking

While prostitution’s claim as the world’s oldest profession has been widely discredited, it could easily assume a replacement title as the occupation that has withstood the most controversy for the longest period of time.

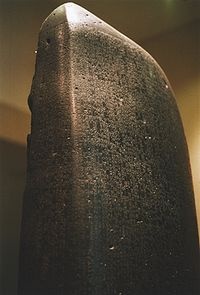

PHOTO: The Code of Hammurabi preserved on a stone "stele."

Source: wikipedia.org (accessed Aug. 29, 2013)

The earliest account of prostitution can be found in the list of occupations included in the Sumerian Records, dating back to 2400 BCE. Due to the context of its placement in this list, prostitution may have been associated with temple service work; thus, it would have likely been regarded as an acceptable and legitimate profession, a sentiment that was reiterated less than a century later in the neighboring region of Babylonia when the legal rights of a prostitute were recorded in Hammurabi’s Code.

Despite these seemingly promising origins, women employed in this profession soon began experiencing regulations. In 1075 BCE, The Code of Assura enacted a legal requirement for all women to wear veils in public, with the exception of prostitutes who, as a means of differentiation, were legally prohibited from doing so.

Prostitution received its first prohibition status in the late 500s when it was criminalized by the Visigoth King of Spain for being incongruent with Catholic values. In accordance with this decree, any girls or women found guilty of prostitution were flogged extensively and exiled, usually the equivalent of a death sentence. In contrast to these severe repercussions, the purchase and subsequent engagement in sex acts was not unlawful and male clients were not penalized.

PHOTO: National Police Gazette - A drawing titled “The Genius of Advertising” from an 1880 issue of the National Police Gazette shows men outside a brothel gazing at pictures of some of the attractions awaiting them inside.

In the United States, prostitution remained federally permissible and was regulated solely by the state until 1910. In 1900, a citizens’ group called The Committee of 15 was established to investigate and lobby against the existence of prostitution and gambling in New York. In their 1902 report,“The Social Evil,” the group established their opposition to the regulation of prostitution, proposing instead a number of alternative solutions to the perceived problem. Among their recommendations were “improvements to housing, health care, and increasing women’s wages.”

The early twentieth century was marked by sudden widespread concern that sex trafficking had become a significant issue within the United States. Such concern was sparked in part by federal action in opposition to forced prostitution, such as the Immigration Act of 1907 barring female immigrants entry into the U.S. for “immoral purposes,” the establishment of a commission investigating correlations between immigration and prostitution, and the rapid growth of the American Purity Alliance’s international campaign against forced prostitution.

PHOTO: Sign reads: “WANTED: Sixty thousand girls to take the place of 60,000 white slaves who will die this year.”

http://www.nupoliticalreview.com/2018/03/02/a-notorious-traffic-a-history/

In 1910, Congress passed the Mann Act. This act, widely referred to as the White-Slave Traffic Act, resulting in the criminalization of knowingly transporting women and girls across state or federal borders for “prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose,” and also making the coercion of women and girls for “immoral acts” a federal offense.

The Congressional decision to implement federal law regarding commercial sex, a legislative topic previously reserved for state-level regulation, seemed to result in the ignition of the public’s already sparked concern. Additionally, news magazines, a number of which were newly capable of national distribution, further fostered public concern by producing an incessant stream of stories recounting alleged occurrences of immigrant women trafficked into the country and American women forced into prostitution by male immigrants.

The consequential societal obsession with the “white-slave trade” led to the marriage of prostitution and sex trafficking in both the public eye and federal legislation. Whereas prostitution had once been understood to be a profession, although controversial, the sensationalization of “white slavery” created the inaccurate belief that all sex workers are trapped within the industry and desperate to escape.

PHOTO: Migrants from Guatemala stream into the United States by way of human trafficking networks through Mexico. Reuters/Corbis

The difference between a sex worker and a sex trafficking victim is a critical distinction to understand. A prostitute is broadly defined as a person who “[engages] in sexual activity in exchange for money or other compensation.” In contrast, as indicated by the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000, a victim of sex trafficking (specifically, severe forms of trafficking) is a person who is “induced [to perform a commercial sex act] by force, fraud, or coercion.”

The result of this conflation has been the seemingly increasing level of difficulty creating legislation that is capable of effectively working to rescue those trapped in a cycle of exploitation and abuse while also working toward achieving the safety and protection of those within the industry by free, personal choice.

While a number of countries have made the decision to nationally legalize prostitution in recent years, and despite the fact that regulated prostitution is legal in certain parts of Nevada, the United States government has continued to hold a strong position against prostitution throughout much of its history.

The primary argument against legalizing prostitution is the belief that the economic theory known as the scale effect will occur as a result. According to this theory, legalization will cause the prostitution market to experience rapid growth, resulting in a subsequent spike in demand. While demand may initially be met by legal prostitutes, the scale effect theory proposes that it will surpass what can be provided by these workers and will create a similar spike in sex trafficking in order to satisfy that demand.

While a number of reports support this theory, including a 2012 analysis of 150 European countries and a 2005 study of areas in Australia that had decriminalized sex work, a number of counterarguments still exist. Perhaps one of the most compelling is based on the current nature of the sex industry itself.

PHOTO: President Trump signed a set of controversial laws enabling state and federal authorities to pursue websites that host sex trafficking ads in the Oval Office on April 11, 2018. Yvonne Ambrose of Chicago, (left) was in attendance. Her 16-year-old daughter was killed after being prostituted on Backpage.com.

Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Due to the criminalization of sex work in the United States and most other regions, the sex trade industry is forced to operate within a black market, resulting in the formation of cartels and, according to many arguments, actually increased violence within the industry. Additionally, criminalization of the industry increases the stigma against sex workers, whether they are in the industry by choice or coercion. This stigma can also result in increased violence and make it more difficult for sex workers to gain the resources they need, whether those resources be to keep them safe or for them to leave the industry altogether.

Arguably the most important issue regarding the safety of sex workers is the fact that due to the criminalized nature of their work, many do not feel safe reporting crimes committed against them to law enforcement. This barrier between sex workers and the officials who can help them and prosecute their perpetrators (including traffickers) makes it increasingly difficult for law enforcement to identify traffickers and keep sex workers safe.

Another issue is the fact that sex workers lack representation. When laws are created to keep them safe or to minimize trafficking, the actual impact may have the opposite result. This was seen recently in the creation of FOSTA, the act which holds websites available for the content posted on them.

PHOTO: Protester holds a placard supporting sex workers in London. Barcroft Media via Getty Images

FOSTA was created to help minimize sex trafficking and online child exploitation by making websites like Backpage, a website infamously known as a source of solicitation, responsible for their content. While this legislation is working to keep trafficking victims from being sold in the sex industry, it has also resulted in a negative impact on sex workers due to the fact that many sex workers who are in the industry by choice are now unable to find work online. Many of these workers have returned to street-level prostitution, where they are more vulnerable to exploitative pimps and traffickers.

Regardless of where we stand on the issue of legalization, we must be sure to include sex workers in the legal decisions that affect them. If our true goal is to protect these women, then it is of the utmost importance that we allow them a voice in these decisions, and ensure that the laws we are putting in place truly have their best interest in mind.

About the Author

Morgan Wiersma is a student at Chicago City Colleges, where she plans to finish her Associate in Arts this spring before beginning to pursue an undergrad in Creative Nonfiction and Social Sciences. She calls her cozy apartment in downtown Chicago home and lives with her dwarf rabbit, Lola. A coffee enthusiast and avid writer, Morgan also enjoys small art projects, tea candles, and over-sized flannel shirts.